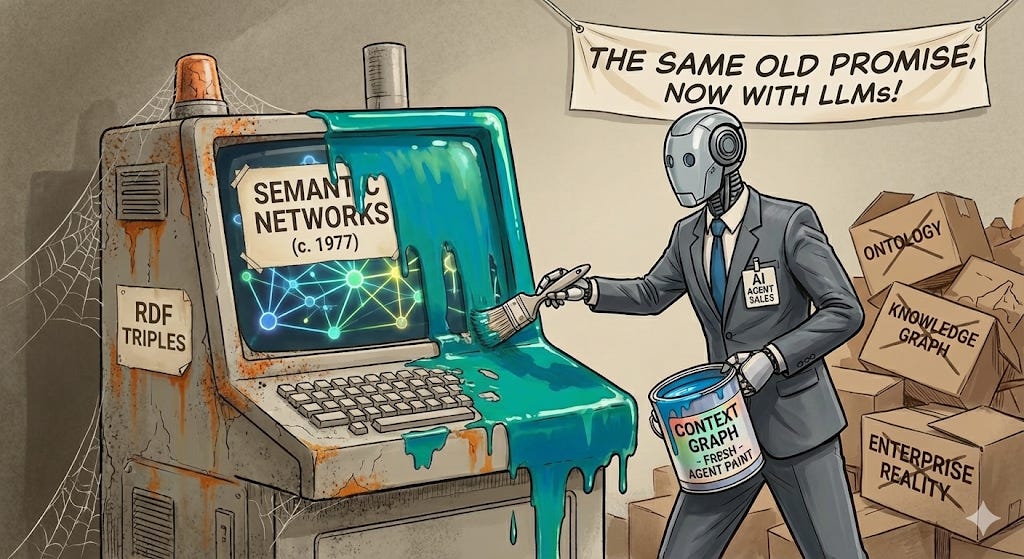

Context Graphs are the New Old Thing

Agentic Pixie Dust for Organizational Chaos

“Context graphs” are being marketed as the missing substrate for agentic AI: model enterprise reality as a semantic graph, retrieve the relevant subgraph at runtime, and let the model “reason” over something more disciplined than a bag of text chunks.

This is not a new idea. It is a familiar promise with a new sales wrapper.

In the 1970s, semantic networks were already popular, already seductive, and already disappointing. By 1977, the critique was explicit: semantic nets never live up to their authors’ expectations of expressive power and ease of construction; the “formalism” is not the panacea people want it to be. The dream was always the same: encode meaning as structure; let inference do the rest. The bill was always the same: meaning is social, time-bound, contested, and expensive to maintain.

The modern version swaps out “semantic net” for “context graph,” adds a LLM at the edge, and calls it infrastructure.

The graph substrate is old. The costume changes.

If someone says “context graph” and means anything concrete, it usually collapses to some combination of:

RDF-style triples (subject–predicate–object), because it’s the simplest lie you can tell that still looks like structure.

OWL-ish typing (classes, properties, restrictions), because eventually someone wants “real semantics,” and OWL is where that road leads.

A query layer (SPARQL, Gremlin, Cypher, or a bespoke retrieval API), because the entire point is to pull a subgraph under constraints.

A retrieval+assembly step that converts the subgraph into a prompt/tool plan for the model.

That stack is not novel. It is the Semantic Web playbook, remixed into an agent narrative and shipped as “memory.”

The new driver is not semantics. It’s capture.

The strongest proponent argument is not “graphs are magic.” It’s that agents create a natural capture point.

If an orchestration layer sits in the execution path, it can emit a decision trace at commit time:

inputs considered

policies evaluated

exceptions invoked

approvals obtained

rationale fragments

the final state written back to systems of record

That matters, because the single most consistent failure mode across decades of semantic systems is simple: the context was never captured. You cannot graph what you do not have. You can infer a story from exhaust, but inference is not provenance.

The correct architectural instinct here is “capture-first, structure-later.” Store the raw trace. Delay schema tyranny. Derive triples, summaries, and edges downstream. Structure is a view, not the asset.

The old failure modes are still the load-bearing ones

1) The ontology bottleneck didn’t disappear. It got renamed.

Call it “ontology,” “schema,” “vocabulary,” or “lightweight taxonomy.” The constraint remains: you need stable meaning across systems and teams.

Most enterprises can’t keep a CMDB coherent. They will not suddenly maintain an OWL-grade conceptual model of their entire operating reality. The path from “a few useful edges” to “enterprise semantic coherence” is where these projects die—slowly, politically, and expensively.

The innovation theater move is pretending you can avoid this by being “schema-light.” That just pushes semantics into retrieval-time heuristics and confidence scores. The meaning debt remains; it simply moves to a different balance sheet.

2) Time breaks naive graphs, and “who” is the sharpest knife.

A non-temporal graph is a present-tense hallucination engine.

Most of the questions a context graph is supposed to answer are time-bound:

who owned the service during the incident

who approved the exception last quarter

what policy was in force when this control was attested

what depended on that system before the migration

Enterprises mutate continuously: reorgs, renames, rotations, entitlement drift, tooling churn. A current-state graph answers historical questions with today’s org chart and today’s access model. That yields confident historical lies with impeccable syntax.

If time is not first-class—valid-time vs transaction-time, event-sourced lineage, versioned identity—then “context graph” is not governance infrastructure. It is institutional misinformation with a graph database.

3) Provenance is not optional; it is the difference between “helpful” and “hazardous.”

A graph without provenance is a rumor mill with better posture.

Edges need:

source pointers

timestamps

confidence and conflict representation

normalization rules

reconciliation behavior when sources disagree

Without that, the graph looks authoritative while behaving like a stitched collage of partial truths.

4) “LLMs make this easy now” is true in the wrong way.

LLMs can help extract structure. They can label entities, infer relations, generate candidate triples, and rewrite trace fragments into legible summaries.

They do not remove the need for:

capture at execution time

semantic stewardship

temporal correctness

conflict resolution

LLMs reduce labor in the middle. They do not remove the constraints at the boundaries.

The corrected thesis

Context graphs work when three conditions hold:

The system sits in the execution path and captures decision traces at commit time.

Raw traces are treated as the primary asset and structure is derived downstream.

Time and provenance are first-class so “who/why/when” are not silently overwritten by present tense.

Everything else is the same old promise with new packaging: a graph that claims to encode reality while avoiding the uncomfortable truth that reality is negotiated, time-indexed, and expensive to keep true.

Context graphs are not novel

They represent the latest instantiation of a persistent pattern: marketing institutional discipline—semantic consistency, cross-system integration, active stewardship, rigorous provenance—as a magical AI substrate that obviates the need for organizational transformation.

Sometimes graph topology genuinely aligns with problem structure. More frequently, it constitutes a procurement-legible narrative that permits teams to evade substantive challenges: incentive realignment, decision rights clarification, elevation of knowledge management from incidental byproduct to maintained asset class.

The graph is not the product.

The product is the institutional capacity to maintain the graph’s correspondence with reality—the unglamorous, politically complex, expensive work of keeping it true.

And that capacity, as it turns out, cannot be purchased. It must be built, defended, and sustained through deliberate organizational investment. This mimetic variant mistakes the representation for the capability, the artifact for the discipline.

We’ve seen this movie before. The ending doesn’t change just because we’ve upgraded the special effects.